Christmas 1848 Slave Escape

Slave Resistance

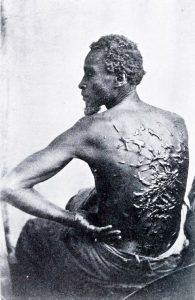

In the past, US history books certainly included the fact that the US once allowed humans to be bought and sold as property, yet at the same time those books excluded the fact that slaves never stopped trying to escape and often organized revolts against their involuntary servitude.

Methods of escape were always desperate but often ingenious. One, Henry “Box” Brown, mailed himself north in a wooden crate.

Christmas 1848 Slave Escape

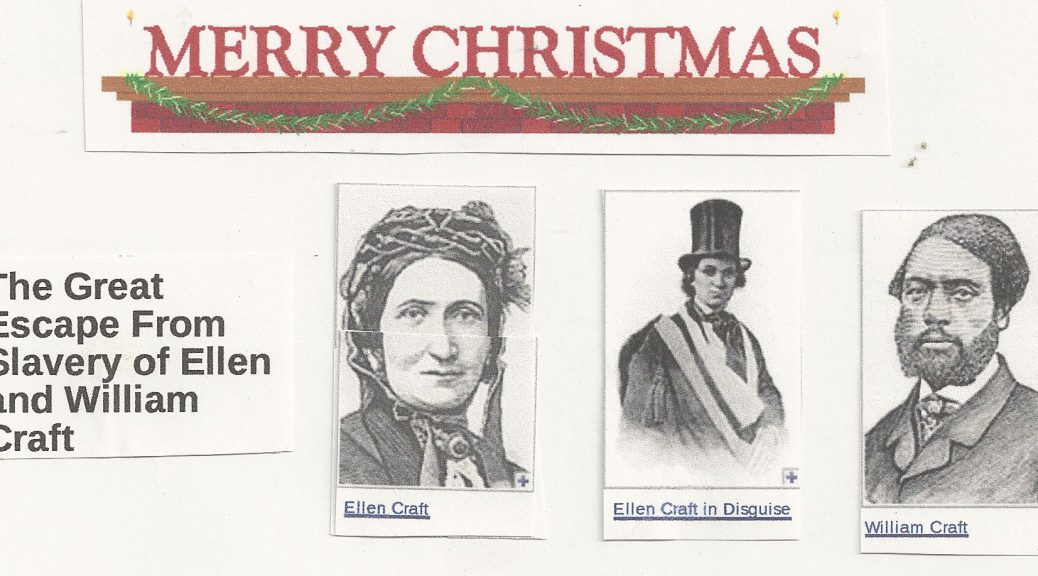

William and Ellen Craft

William was born in Macon, Georgia to a master who sold off Craft’s family to pay gambling debts. William’s new owner, a local bank cashier, apprenticed him as a carpenter in order to earn money from William’s labor.

Ellen Craft was born in Clinton, Georgia and was the daughter of an African American biracial slave and her white owner. Because of her light complexion, strangers often mistook Ellen as white. Bothered by such a situation, Ellen’s plantation mistress sent the 11-year-old Ellen to Macon to the mistress’s daughter as a wedding present in 1837, where Ellen served as a ladies maid.

It was in Macon that William and Ellen met.

In 1846 their owners allowed Ellen and William to marry, but they could not live together since they had different owners. Obviously unhappy with that forced separation and the fear that their masters could sell any children, the couple started to save some of the meager wages their owners allowed them to keep and William and Ellen planned an escape.

Christmas 1848 Slave Escape

Escape

In December 1848, they attempted just that. Because they were “good” slaves, their masters permitted them passes for a few days leave at Christmastime. Those days would give the couple time to be missing without notice.

As it was not customary for a white woman to travel with a black male servant, they decided that they would escape by traveling as a white male and his black servant.

On December 21, 1848, William cut Ellen’s hair and put her right arm in a sling. Not being able to read or write, but knowing others would ask Ellen, the “white male” to sign papers at check points along their way, an injured arm prevented signatures.

Also William partially covered Ellen’s face with a “bandage” to further hide her female appearance. Ellen dressed in trousers she’d sewn and a top hat.

Christmas 1848 Slave Escape

The perilous journey

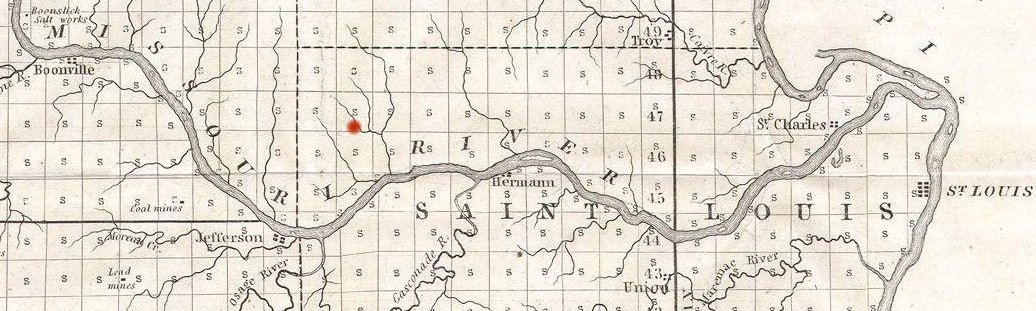

They went by train from Macon to Savannah; a steamship to Charleston, South Carolina; another steamer to Wilmington, North Carolina; a train to Fredericksburg, Virginia; another steamer to Washington, D.C; a train to Baltimore, Maryland, and thence to Pennsylvania.

They had to travel separately the whole worrisome journey with constant fear that someone would see through their ruse and reveal them.

That fear was almost realized several times, but they nonetheless arrived in Philadelphia on Christmas day, 1848.

The Crafts moved on to Boston, which had an established free black community and a well-organized, protective abolitionist activity. William, a skilled cabinetmaker, started a furniture business.

Christmas 1848 Slave Escape

Fugitive Slave Act

In 1850, the US Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act which made it a crime for residents of free states to harbor or aid fugitive slaves like the Crafts. The act also rewarded anyone for assisting slave owners by apprehending their fugitive “property” and returning them to slavery.

Two slave catchers, Willis Hughes and John Knight, traveled north to capture the Crafts. The town of Boston sheltered the couple and kept them away from the bounty hunters.

Hughes and Knight returned south, but still feeling unsafe anywhere, the Crafts moved to England in 1851.

Christmas 1848 Slave Escape

West London

The Crafts settled in West London where they eventually raised their five children: Charles Estlin Phillips, William, Brougham, Alfred, and Ellen. They continued in the abolitionist movement by lecturing in England and Scotland.

In 1860 they published Running a Thousand Miles For Freedom.

During their nineteen years in England, the Crafts taught, ran a boarding house, and William created commercial and mercantile agreements in West Africa.

Christmas 1848 Slave Escape

Return to the US

They returned to the United States in 1870 and settled near Savannah, where they opened the Woodville Co-operative Farm School in 1873 to teach and employ newly freed slaves. The school closed after a few years because of a lack of funding.

In 1890 William and Ellen Craft moved to Charleston to live with their daughter. Ellen Craft died there in 1891. William Craft died in Charleston in 1900.

Here is a link to a PDF of their book: Running a Thousand Miles